Welcome springtime

March 6th – May 4th, 2019

INFO

By Jimena Ferreiro

I know that we are bidding summer farewell and that it will be many long months before spring comes around again. The calendar tells us that the days will soon grow shorter and the temperature drop. But Buenos Aires has been getting more tropical by the year, and the winters are milder and milder. Besides, spring is also a state of mind.

Festive and forever young, springtime is promise and eagerness; it is sexy and lighthearted, like Venuses throughout art history. It is first light and potential, endlessness and finitude. A vital cycle that ends only to begin again, and so on forever.

I would venture to say that spring holds a secret: the blessing of beauty that, as is always the case, hides its darker side.

The exhibition that opens today at the Nora Fisch gallery is a “cover” of the exhibition Bienvenida primavera held at the Centro Cultural Ricardo Rojas in September 1991. It is the first exhibition of Alfredo Londaibere’s work to be held after his death in April 2017. The reference to the earlier exhibition is a bit arbitrary—but not entirely: Alfredo took part in that show, and he took over from Jorge Gumier Maier as the curator of the Rojas gallery in 1997 (he held that post through 2002).

Bienvenida primavera was the first group show that Gumier co-curated with Magdalena Jitrik. Its aim was “ecumenical”: it set out to link different generations of artists and different poetics at a moment that would prove a watershed in Argentine art. Soon, a series of adjectives would be used to describe the group of artists associated with the Rojas gallery, terms like “light,” “pink,” and “sissy” art were among those that appeared in reviews and criticism of the time—but that’s common knowledge.

Bienvenida primavera was the first show to feature work by Omar Schiliro. He began making art when he learned that he had the HIV virus, which would lead to his premature death in 1994. Magdalena Jitrik told me some time ago that, in her view, what was really at stake in what would come to be known as Gumier’s “domestic curatorial model” and like conceptual eccentricities was something much more vital: the love story between Gumier and Omar, and Gumier’s desire to build a context where Omar’s work would shine. Curating as a pulp novel—isn’t this a nicer way to think of it?

This show in the Nora Fisch gallery is the direct heir to that affective network. While it does partake of tribute, in a way, it is more like to a vital celebration of bold colors and forms and, naturally, the party’s end. Because many of Alfredo Londaibere’s most remarkable works hold within a beauty that is sensual and airy, but also agonizing and tragic, like cans squashed on a dance floor or confetti and glitter once they have lost their sparkle.

That is, perhaps, one of the visual keys to the nineties: a dimmed and deformed shine like the strip of nickel silver on some of his paintings, turning them into votive offerings in a state of decay. A beauty that stubbornly resists fading and that, like springtime, reinvents itself cyclically.

“I see nature as oneness of form and meaning,” said Alfredo. “I feel that I belong to that, that that is me. Part and whole. Aware of the continuity, of seamlessness as truth.” Alfredo believed that painting could capture all of an artist’s expressive ability and all of art’s truth. He explored it over the course of his lifetime, turning it into a tool for formal experimentation as well as a means to reach a spiritual state that became more and more patent in his work in the 2000s.

His spirituality was expressed in a methodic, intimate, and solitary way of making; his aesthetic agenda was governed by intuition, pleasure, and contemplation in an ethos of austere and disciplined work that gradually steered him away from the routines of contemporary sociability. He eventually found in the image a new reality in which to display the secret language of things.

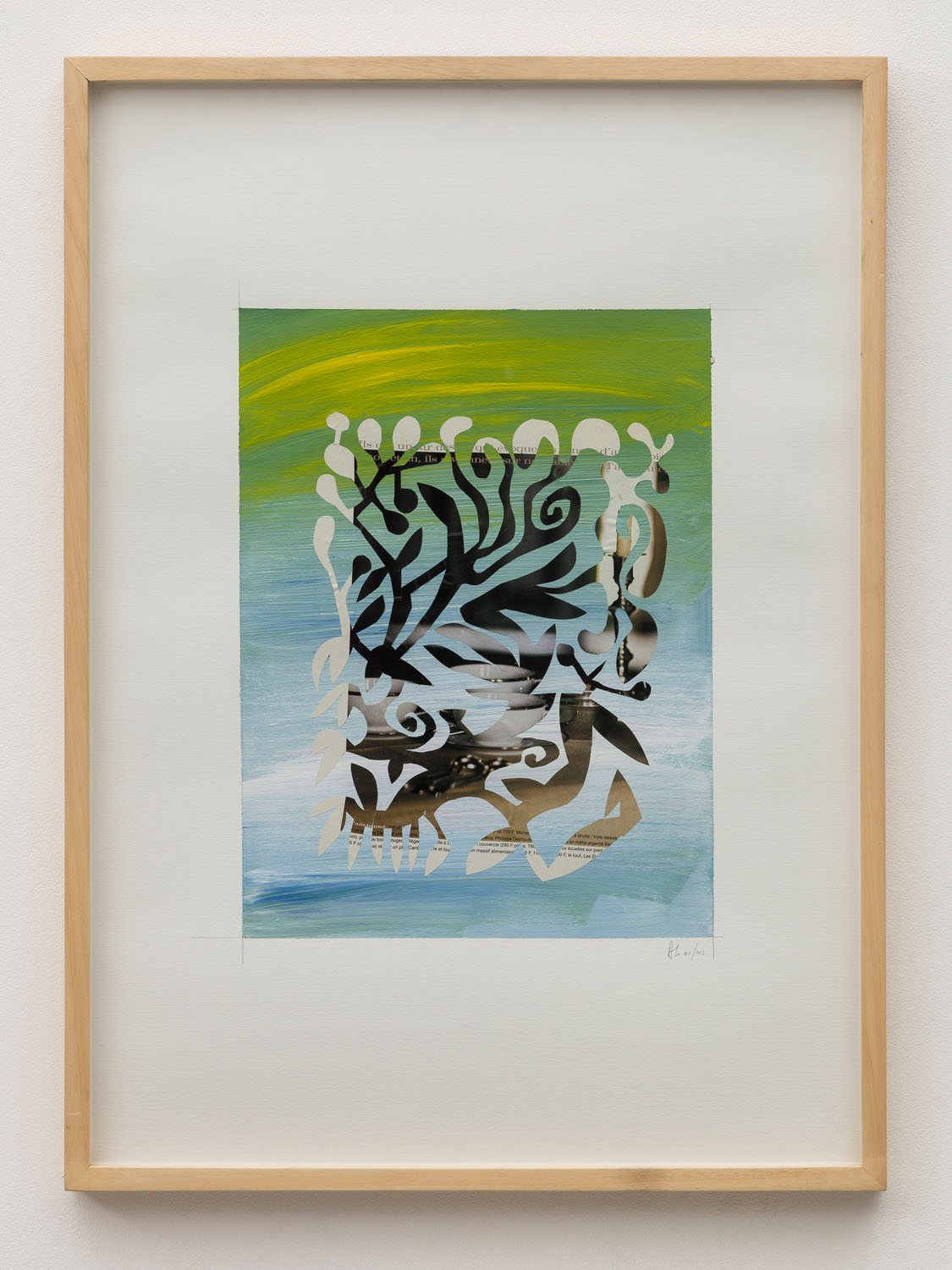

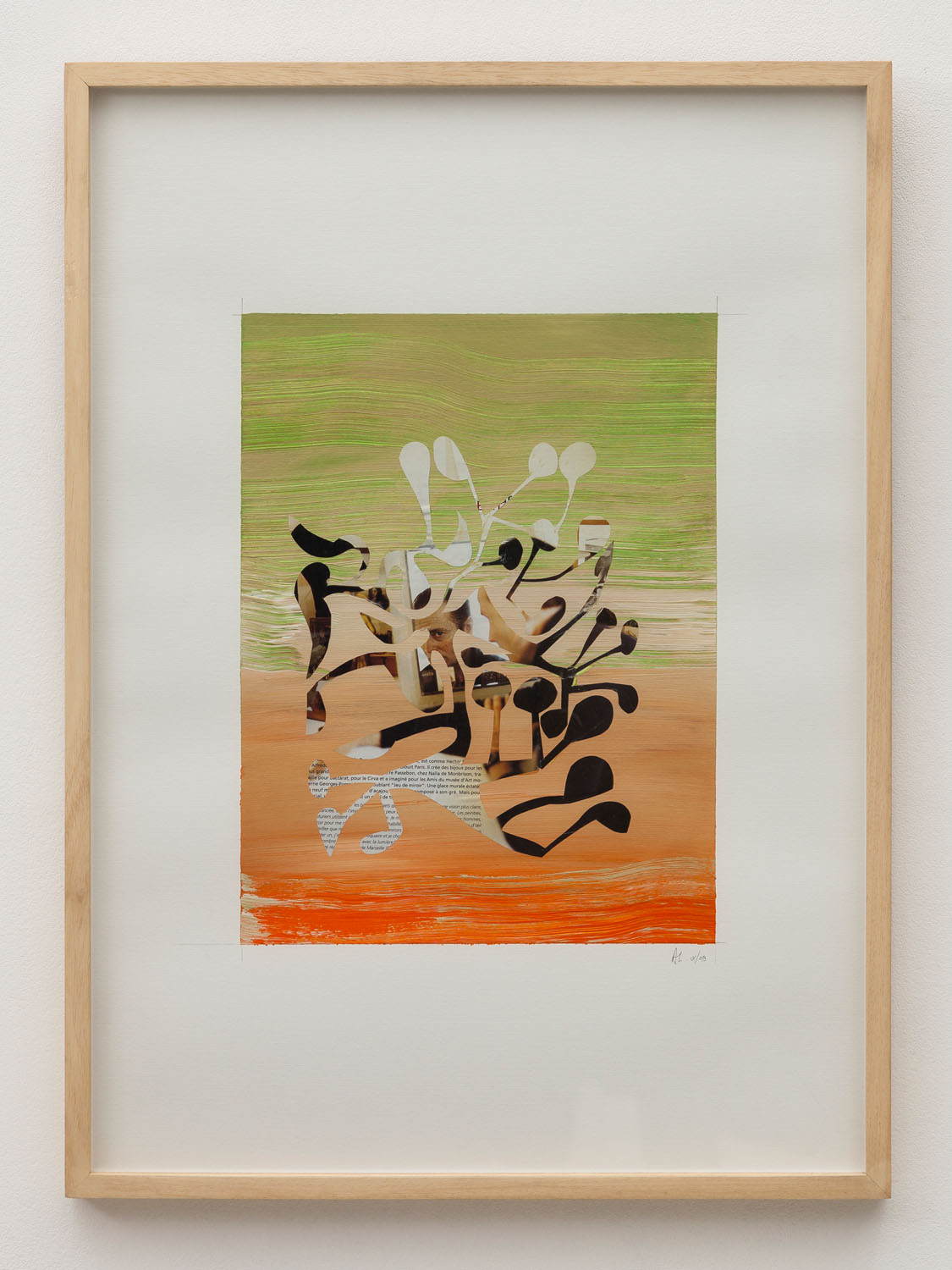

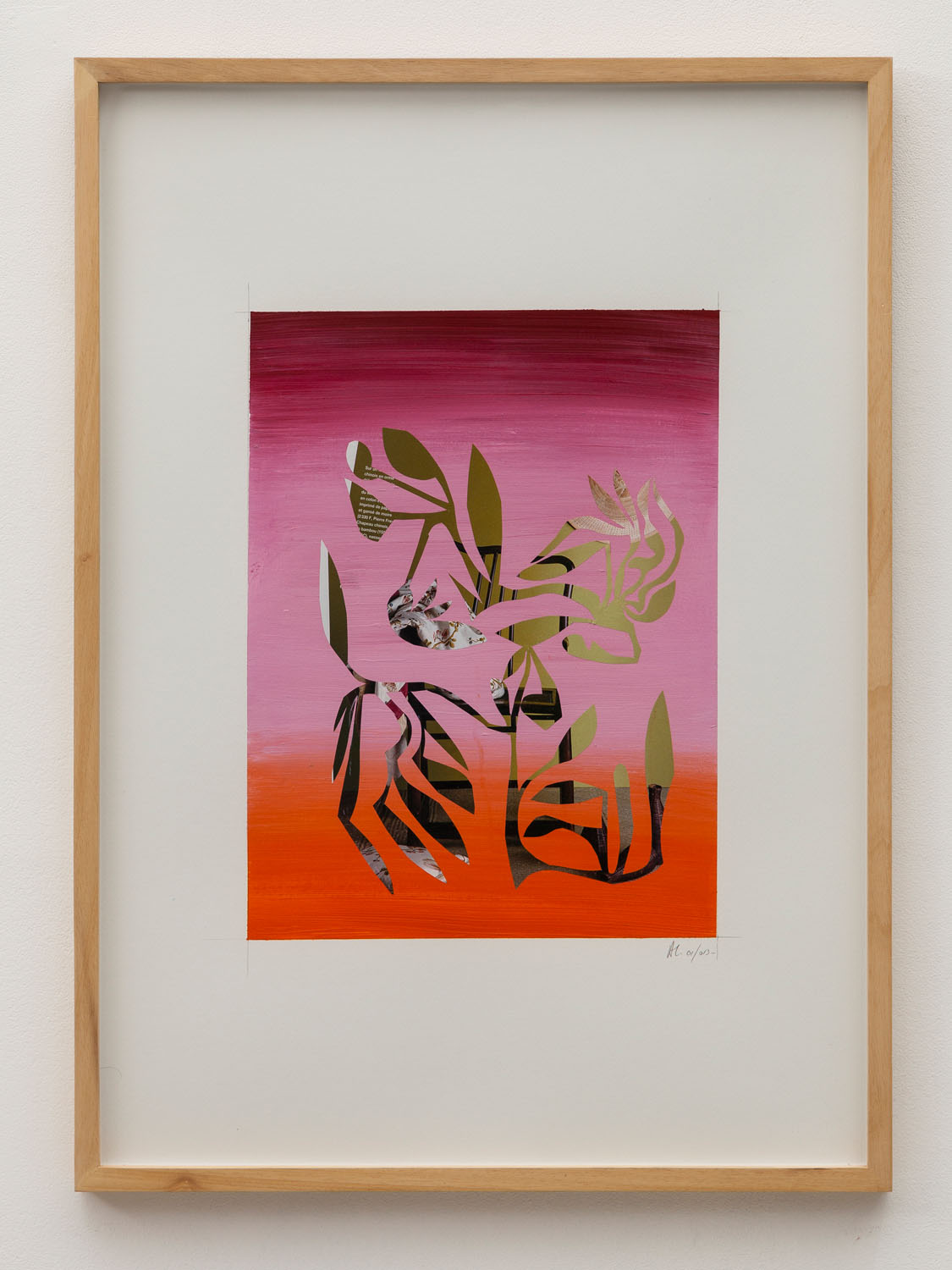

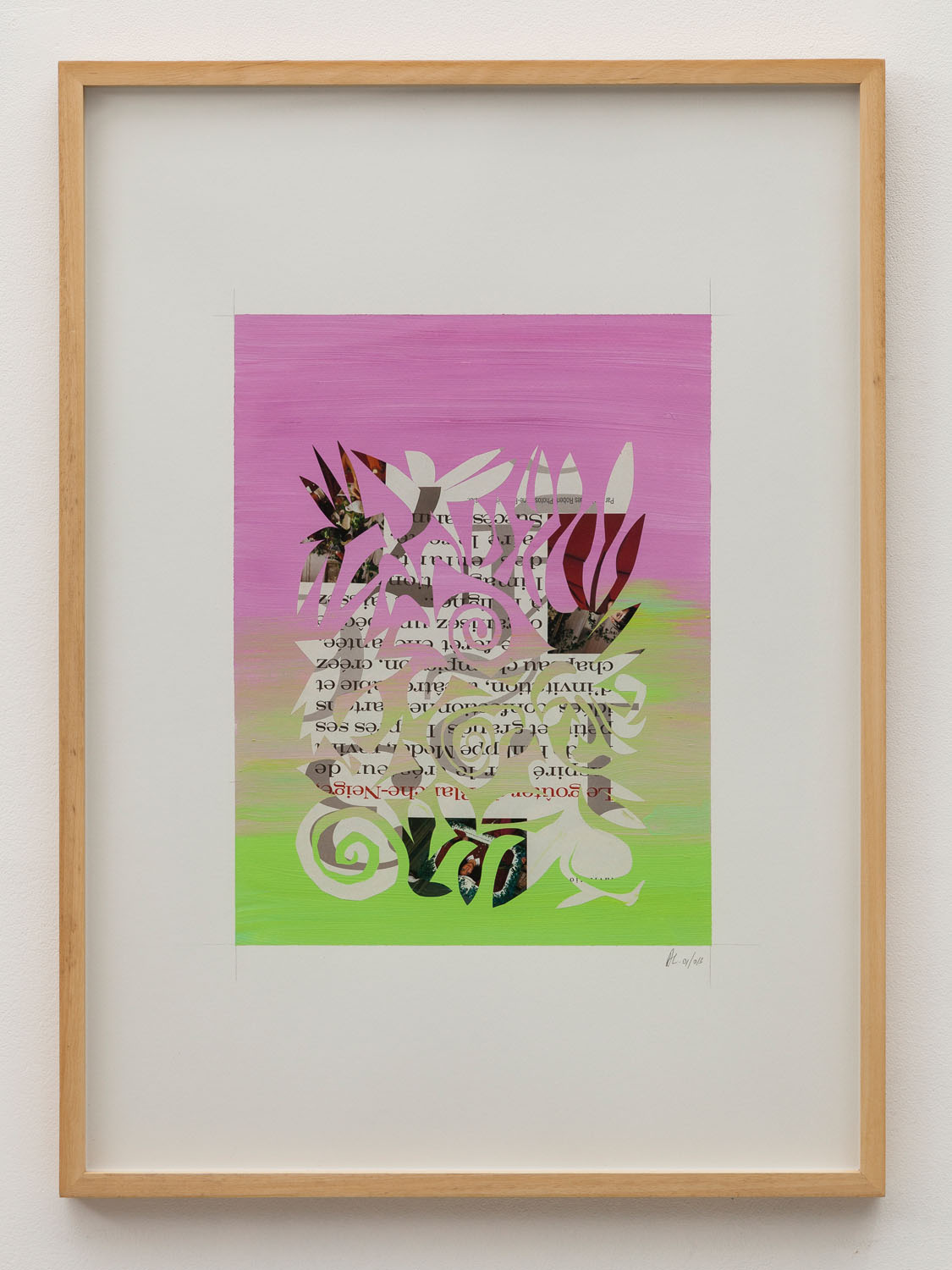

Bienvenida primavera features a series of collages produced in 2013. The gradient of bold, spring-like colors in each work surrounds a central shape rendered with a single cut, a form with fantastic touches that draws inspiration from plant life. His skillful use of the scissors—like a single freehand stroke—is remarkable. The combination of the precision of the cut and giving himself over to the forms that the blade would discover enabled him to turn the photographs he found in the magazines he kept like an image bank into truly exquisite shapes. There is a distant reference to the European surrealists artists he admired so, to Juan Batlle Planas and his Radiografías paranoicas [Paranoid X-Rays], and—more recently—to Fernanda Laguna, with whom he shared the utopian first years of Belleza y Felicidad, that cultural general store that allowed him to make a living from selling his temperas, which were quite affordable in the years around the 2001 financial collapse.

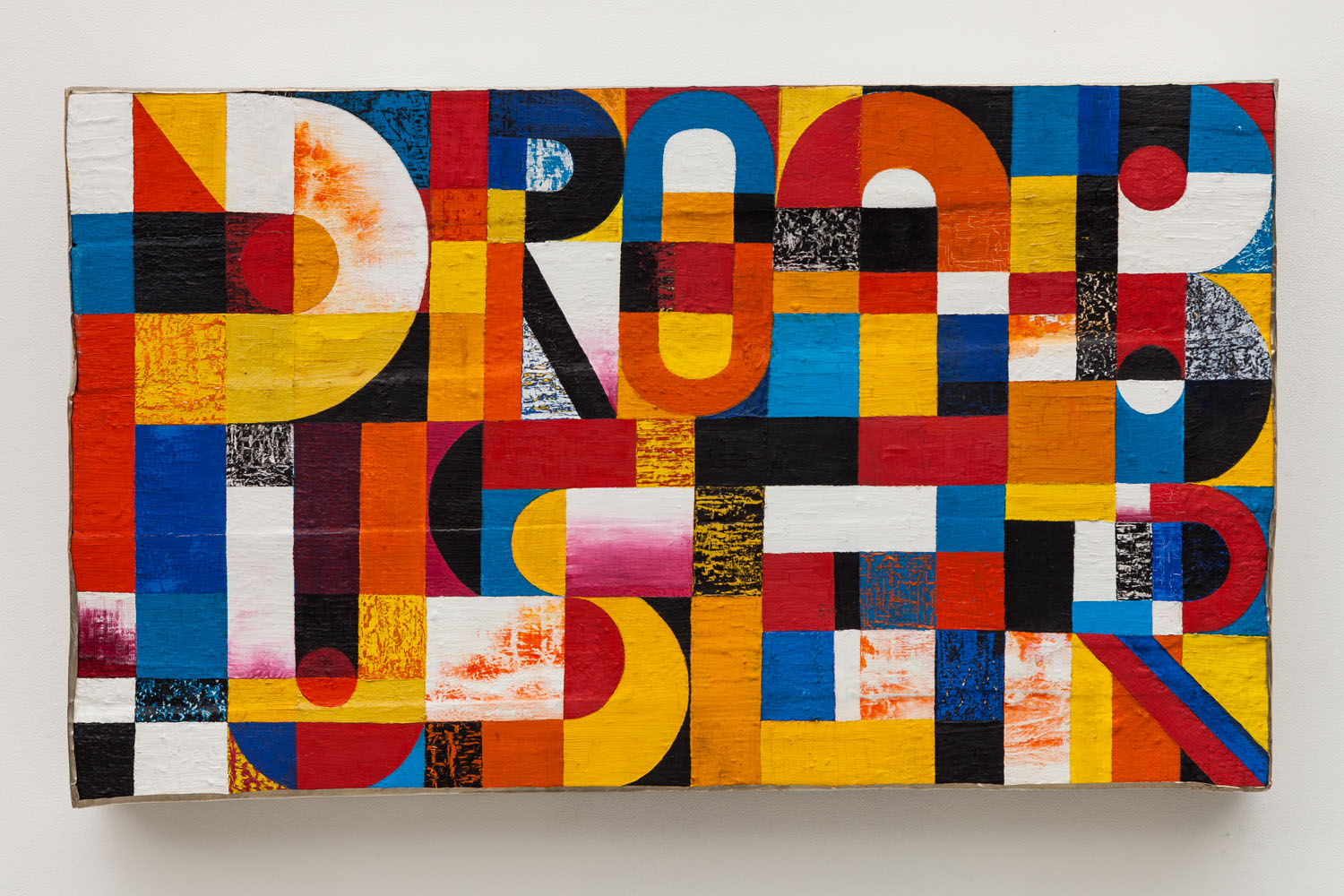

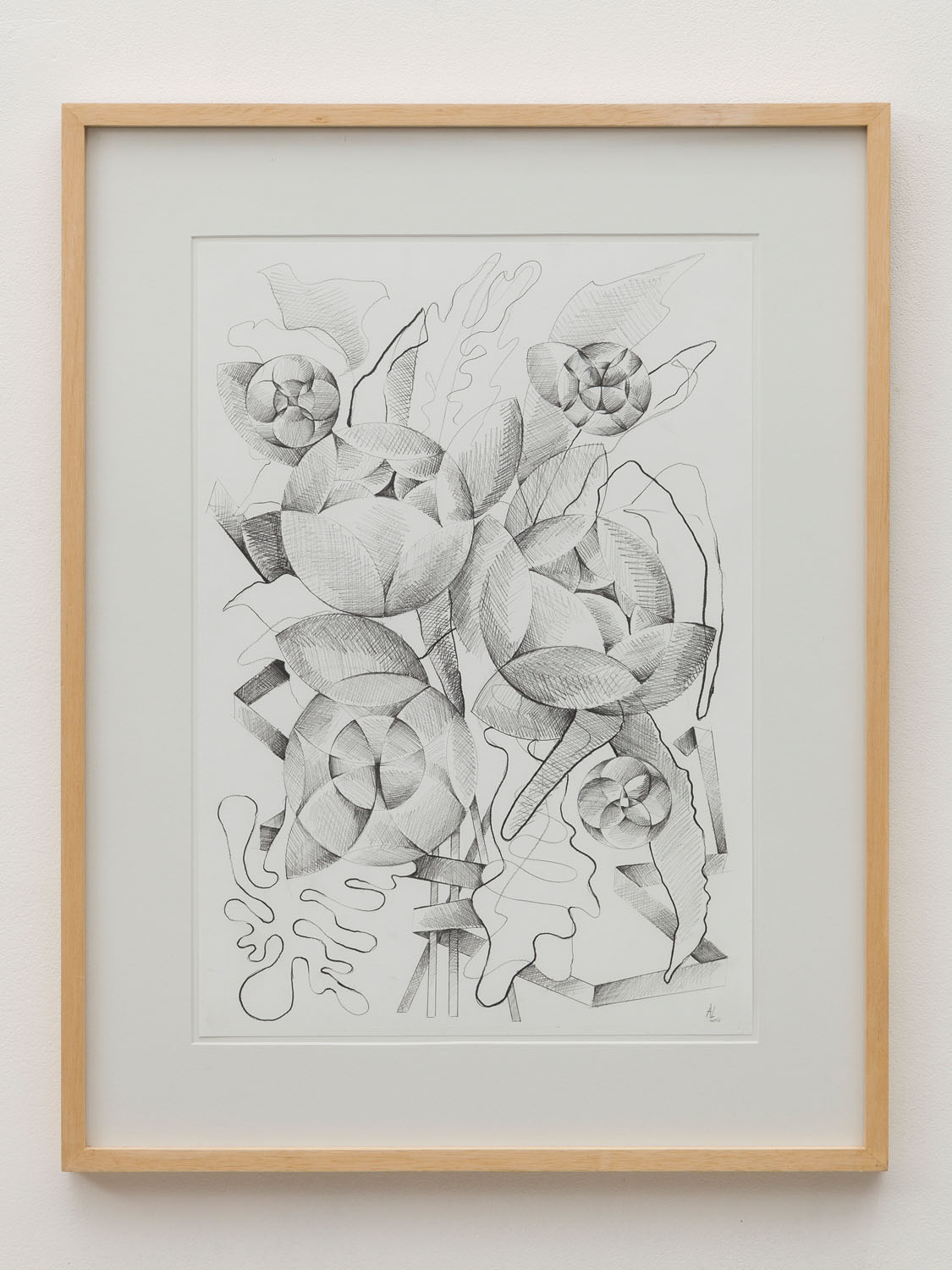

We have also included in the show a group of medium-sized paintings that he made in 2016, just a few months before his death, works in which geometry, ornamentation, and botany coexist in particular fashion. Those flower vases he began painting in 2013—startling because so much larger than most of his work—deliberately displayed a clash of pictorial styles that he would describe as the “battle of the isms”: the analytical precision of cubism versus the aggressive brushstroke of expressionism.

Welcome, Alfredo Londaibere, once again, to this great theater of painting that holds all the secrets you safeguarded in the ciphered beauty of your art.

Buenos Aires, summer 2019

Notes on Alfredo Londaibere’s life

An artist and teacher, his last name was actually Londaitzbehere, and he signed as such until the early nineties, when he began using the name for which he is known in the art world.

He began studying with Carlos Kurten in 1967; he studied with Araceli Vázquez Málaga from 1973 to 1977. He exhibited his early works in bars and dance clubs in the eighties. Towards the end of that decade, he began making use of grids and ornaments in series of paintings and collages that parodied the expressionist pictorial gesture.

He was part of the group of artists clustered around the art gallery at the Centro Cultural Ricardo Rojas under the curatorship of Jorge Gumier Maier from the time of its founding. His first solo show, Mapas y pinturas, was held there in 1989. A second show of his work, this one curated by Magdalena Jitrik, was held in the same venue in 1991. His works from this period seem to disassemble a forceful masculine pictorial tradition: dripping became a rainfall of colors in grade school-like compositions in paste, tissue paper, and stickers—a visual repertoire that revalorized “feminine handicrafts.”

In 1991, he participated in the first edition of the Beca Kuitca, along with Jitrik, Graciela Hasper, Tulio de Sagastizábal, Daniel García, Daniel Besoytaorube, and others. He was awarded a fellowship from Fundación Antorchas in 1995 to attend the Taller Barracas under the direction of Luis Fernando Benedit and Pablo Suárez. He taught art at the Centro Cultural Ricardo Rojas until the time of his death.

Outstanding solo shows of his work were held at Mun gallery in 1993 and 1994; the Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamericana (ICI) in 1996; the Alianza Francesa in 1998 (curated by Sonia Becce); the Centro Cultural San Martín in 2005 as part of the cycle El artista como curador, coordinated by Batkis; and the Nora Fisch gallery in 2015.

In 1997, he replaced Jorge Gumier Maier as curator of the Centro Cultural Ricardo Rojas gallery, a post he held until 2002. In 2015, he was awarded the first prize in painting at both the Banco Central de la República Argentina prize and by Fundación Andreani prize.

The Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires is currently working on the first retrospective of his production to be held after his premature death in 2017; the curator of that show will be Jimena Ferreiro.